© Benaki Phytopathological Institute

Marinan-Arroyuelo

et al.

70

yield it needed to be supplemented with

some hand weeding (Table 3) or with a post-

emergence herbicide and some hand weed-

ing (Table 2), measures which increased the

weed control costs and decreased the ben-

efit/cost ratio.

With these trials it became clear, there-

fore, that pendimethalin, being a residual

herbicide with a broad weed spectrum (in-

cluding both broadleaf and grass weed spe-

cies) and registered for many crop uses in

Southern European countries, has the po-

tential to provide maximal yield at the best

benefit/cost ratio in many situations

.

In oth-

er situations, in which there may be a need

to combine pendimethalin with supple-

mentary measures in order to get the maxi-

mal yield, the benefit/cost ratio would most-

ly depend on the cost of the supplementary

measures that will be used.

A properly selected post-emergence

herbicide, if available, could be an econom-

ical supplement to pendimethali

n

. Other

researchers have already shown that high

yield in annual crops is better secured if a

pre-emergence herbicide has been used pri-

or to the post-emergence herbicide appli-

cation (Nurse

et al.

2006; Fickett

et al

., 2013).

In all trials of this study, on the other hand,

pendimethalin significantly reduced the re-

quired time of supplemental hand weeding

to avoid yield loss and provided better ben-

efit/cost ratios and labour return values than

using hand weeding alone (which by itself is

not economically justified at current prices in

Southern European countries). Hand weed-

ing may therefore be another economically

justified supplement to pendimethalin.

Furthermore, other specific reasons have

also increased in recent years the impor-

tance of using a pre-emergence herbicide

particularly for the crops examined in these

trials. Most processing tomato growers in

Southern European countries, to achieve a

better management of specific weeds (eg.

Solanum nigrum

), have abandoned direct

seeding and turned to transplanting which

allows the pre-transplant application of a

pre-emergence herbicide (Tei

et al

., 2003).

The onion dry bulb producers, to reduce

production costs and face price competition

in the market, have turned to direct seeding

but with the young onion seedlings being

susceptible to available post-emergence

herbicides they need to use a selective pre-

emergence herbicide for early season weed

control (Tei

et al.

, 1999). In cotton (Giannop-

olitis, 2013), broccoli and other vegetable

crops (Campagna

et al

. 2009), there are no

registered broad spectrum post-emergence

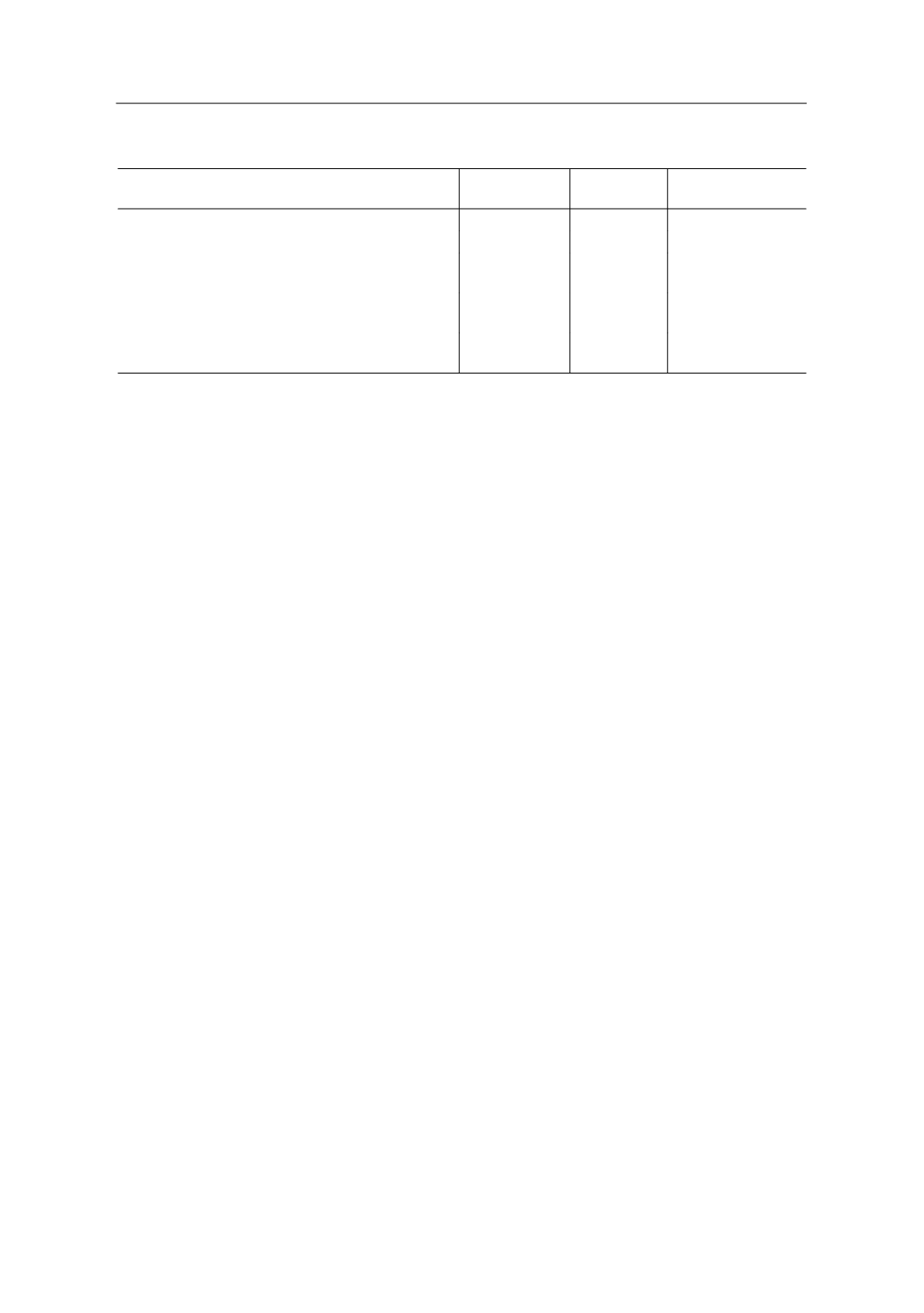

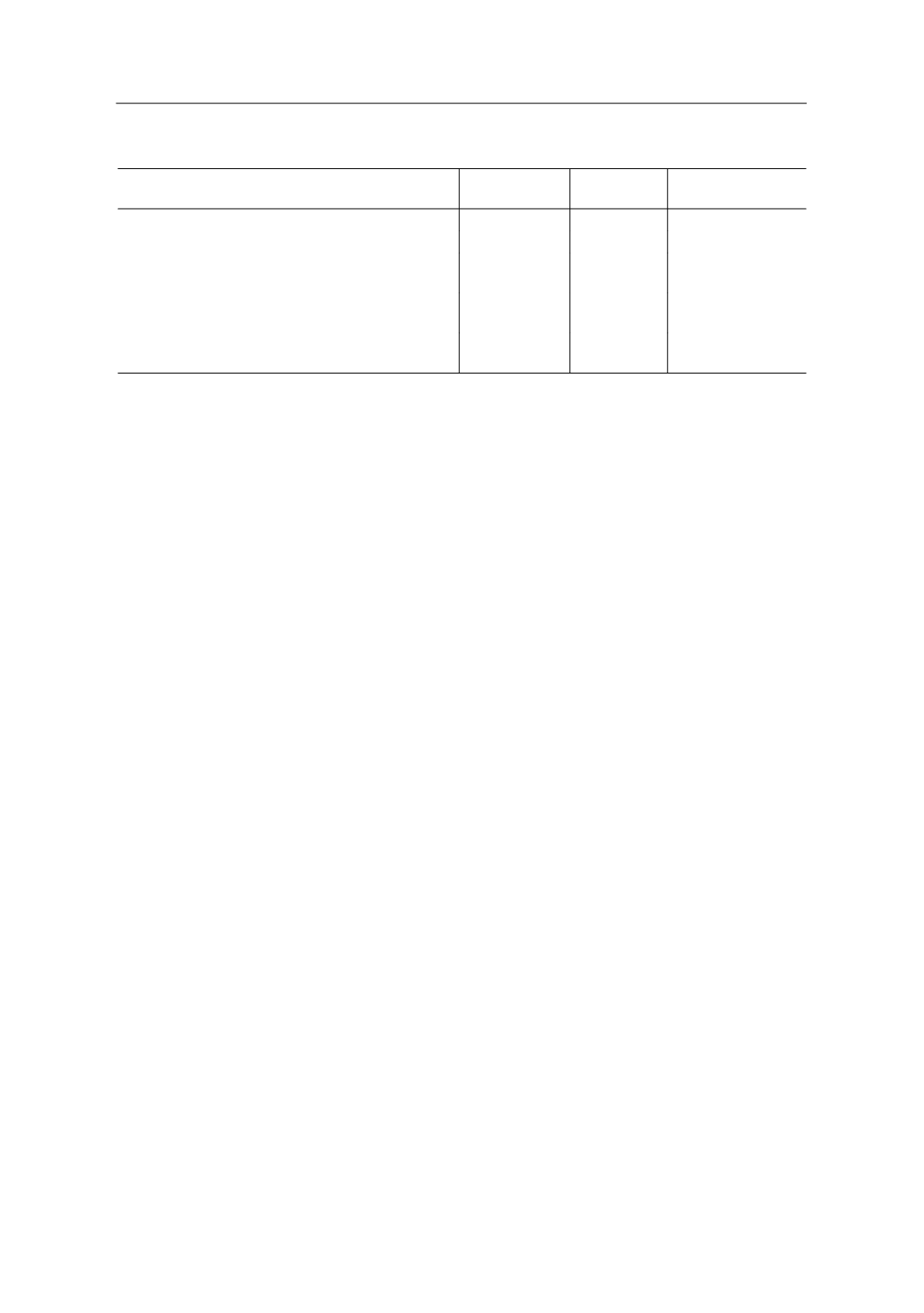

Table 5.

Expected weed control benefit/cost ratio in processing tomatoes using alternative

weed control scenarios*.

Scenarios

Benefit

(€/ha)

1

Cost

(€/ha)

Benefit/Cost

(€/€)

Inter-row cultivations + hand weeding on rows

2

2697.50

650

4.1

PE mulch on rows + herbicides post- transplanting

3

2697.50

476

5.7

Pre-transplanting residual broad-spectrum herbicide

(pendimethalin)

4

2697.50

101

26.7

Pre-tranplanting broadleaf herbicide (oxadiazon)

+ post-transplanting grass herbicide (fluazifop)

5

2697.50

143.5

18.8

Post-transplanting, two herbicide applications (rim-

sulfuron and metribuzin+rimsulfuron)

2697.50

215.8

12.5

* Based on 2011 prices in Greece (first year after decoupling of the EU production subsidies, when the industry paid

for the tomatoes 20 €/ton higher than the previous year).

1

Assuming a 50% gain (32.5 ton/ha) of an average normal yield (65 ton/ha) x 83 €/ton in all scenario

s

.

2

Cost: 200 €/ha for two cultivations + 450 €/ha for two hand weedings.

3

Cost: 350 €/ha for the PE plastic + 96 €/ha for the price of herbicides (metribuzin+rimsulfuron) + 30 €/ha for

application.

4

Cost: 51 €/ha for the price of herbicide + 50 €/ha for the application.

5

Herbicide prices 46+37,5 €/ha and application cost in Greece 30+30 €/ha.